Interview by Jesse Ducker

Interview by Jesse Ducker“Hip-Hop is at its best when it’s angry.”

-Paris

During the early 1990s, Paris was just as angry and inflammatory as any Bay Area rapper out there. But for the Black Panther of hip-hop, it was anger with direction, not anger for anger's sake. With his Rakim-esque flow and dark and brooding soundscape, Paris verbally assaulted corrupt politicians, police, and racist institutions, on albums like

The Devil Made Me Do It, Sleeping With the Enemy, and

Guerilla Funk. They were all integral parts of the period when hip-hop tried to buck the system, rather than suck-up to it.

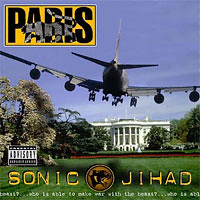

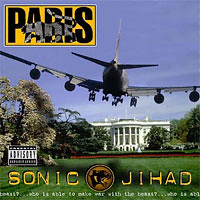

Paris was off the map through the late 1990s and the early 21st century, before storming back on the scene with a vengeance in 2003 with his

Sonic Jihad. One of the boldest statements of the album was its cover, which depicts an airplane hurtling towards the White House, on a kamikaze mission. It was not the most subtle statement ever made, but it was certainly an angry one...

Soon after, Paris officially launched

Guerilla Funk Records, sporting distribution through Groove Attack. He set out to using his label to release material by artists that the few surviving major labels were too scared to touch. Paris’ Guerilla Funk is now home to new records by legends such as Public Enemy, as well as a fresh battery of raging hip-hoppers, like dead prez. And he eventually plans to record a new album’s worth of material himself.

Paris plans on using his labels to put out positive, yet confrontational hip-hop. With a sharp perspective on the music business, media, corporate America, and politics, Paris is charging forward and taking no prisoners. And definitely staying angry.

Shout: So what’s coming out on Guerrilla Funk Records?Paris: We’ve got the Public Enemy album,

Rebirth of a Nation, which should be coming out on January 24. We’ve got an album by Kam, one by dead prez, one by T-Kash [Hard Knock Radio, The Coup]. Then we’ve got the

Hard True Soldiers compilation with all those artists, plus MC Ren, Immortal Technique, Everlast, and Conscious Daughters.

How did Public Enemy end up putting out an album on Guerilla Funk? Chuck D had a few guest verses on the

Sonic Jihad album. I’ve known them for years, so we just worked something out so that they’d put out an album through Guerilla Funk. It was first going to come out this summer, but we held on for a bit. Now we’re going to release it in early 2006 with a few extra songs.

The community of positive rappers is small. There are a few of us out there that can come and say what we say. And there’s only a handful that do it well and I respect as artists. You can say what you say, but that doesn’t make it good listening.

What was it like working with Public Enemy?Working on the Public Enemy album was a labor of love. They’re responsible for a lot of people out there rapping right now. And I’m of course a huge fan of their work.

I think the album is one of their best since at least

Fear of Black Planet. Maybe since

It Takes A Nation of Millions. The way I came at them, I was like, ‘I haven’t felt some of the music you guys have been putting out.’ So I told them if you allow me to have creative control, we can put out this album and I’ll break you off financially. So I produced and wrote everything for

Rebirth. There’s only a stigma of ghostwriting if you let there be one. It’s not like Celine Dion writes all her lyrics. She has songwriters writing her material for her. So it went well; Chuck and Griff got in there and kicked their lyrics, and it came out sounding great.

So just to be clear, you wrote all of the lyrics for Rebirth of Nation?Yeah, but that’s not something we’re hiding.

So how would you describe the state of hip-hop music right now?The sad reality is that artists adjust their music to what labels are looking for. And most major labels want music that will appeal to a large audience. They want escapist material. So you get all these artists making records that haven’t paid dues and are in the game for the wrong reasons.

But corporate America keeps on trying to sell panic in hip-hop music. It’s a subtle type of racism. The music that they market that’s intended for a wide audience is negative and relies on negative imagery to sell. There’s a wider appeal on spending money. So after a while, the streets only want what the corporations are presenting.

The writing has been on the wall for a while. Hip-hop is just about making money to these labels. There’s no drive to create good albums. Now all you have is a single-driven environment, and its sold to the public as the lowest common denominator. The music is made so that it’s palatable to everyone.

So how does that make you feel, as someone who came up in a different time for this music and someone who runs their own label? I don’t trip off of what other labels are doing. Labels are adversarial. I set up my own separate entity. It takes pressure off of what we do.

My label is for anybody that’s fed-up with music now. Fed-up with how music has been turned into a commodity. Tired of the constant drone. Tired of the cookie-cutter approach to music. They want more. I’d like to believe that the music that transcends the hypocrisy is on Guerilla Funk.

So when you sign an artist to Guerilla Funk, how do things work?First of all, I don’t have any artists “signed” to Guerilla Funk. I pay for everything, and let everybody be a free spirit. I just ask that they don’t put out music that’s exploitive or negative. If an artist feels comfortable with the label after they’ve recorded the album, they’re free to come back. But we don’t sign anybody to deals or anything. A lot of the artists are shell-shocked by their experiences on other labels when they come to us.”

So are you surprised with all the trouble that George is facing now as President?Bush has been an ass for years. You can tell that from watching Fahrenheit 9/11. That movie was a two-hour window of truth. But it’s going up against 24hour news network like FOX News that can spend all of its time making false accusations against it. So they will have more effect on the opinions of people who watch the network.

Does George Bush care about Black people? George Bush doesn’t care about most people. If you’re not his neighbor or giving money to his campaign, he doesn’t give a damn about you.

How do you see what you do as being part of the solution? The

Sonic Jihad album cover was intended to be inflammatory. I was the first to be up front with it. The album was a hard-truth cocktail. My records are my tool and my weapon against the system. It’s necessary to push buttons like that. On the intended cover of

Sleeping With the Enemy, I was hiding in a tree, waiting to assassinate the first George Bush. That’s envelope-pushing. You’re not getting that from a lot of acts out there. I could give a fuck less if people like it or don’t like it.

I’ll tell you this: protesting in the streets is an exercise in futility. People don’t even notice it. Now if Scalia comes up floating in the river, I bet people would notice that.