الاثنين، أيار ٠٢، ٢٠٠٥

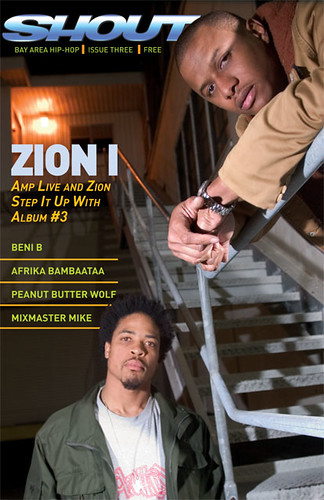

Zion I

By Folklore

Smoking herb certainly alleviates the burden of transcribing a lengthy interview, but it does nothing for writing witty opening lines. Good music gets us through these moments, and Bay Area denizens Zion I–producer Amp Live and emcee Zion–have returned to offer your ears some inspiration in the form of True & Livin’, their third full-length effort.

More significantly, it’s the first album released exclusively through their own label, Live Up, submerging their deep water slang further into both financial and record pools. Amp says, “We were able to work with a couple of people from the first label and put a together a tight infrastructure, so this album, True & Livin’, came off our own label. This is a big project.”

Time management may be a remedial class for detention-prone high schoolers, but it’s also a life lesson that aspiring professionals (musicians or otherwise) should enroll in.

“We had a hectic schedule this year,” recounts Zion. “We went from being in the studio almost every day, to goin’ on tour, to comin’ back, to bein’ back in the studio, to goin’ back out, to bein’ in the studio again to mix and master. And it’s like we really didn’t have too much of a break. With other albums before, Mind Over Matter took like four years to make and Deep Water Slang took about two-and-a-half [to] three years to make; this album took one year. So it’s basically takin’ all of your emotional experiences, takin’ photographs of how you feel, and then tryin’ to compile them and put ‘em together in a presentable way.”

A quick flip through the Zion I photo album illustrates the effort involved in creating and sustaining their career. While a knee-high Amp Live was playing drums and piano for his church and developing beats in San Antonio, Texas, Zion’s formative years were spent memorizing the lyrics to “The Message” and “Sucka DJ’s” in Philly. In 1991, they met while attending Morehouse College in a pre-Southernplayalistic ATL. The two added two other members, the sum of which comprised their first group Metafour. Though inked to Tommy Boy, Amp & Zion opted to split and chase the sun west.

“From the Metafour days till now, I think the real difference is that we just know more about the business,” says Zion. “And we’re more concerned about makin’ things happen correctly, ‘cause back then we didn’t know shit, and we thought we did. We thought all you had to do was make a good record and make a dope video. That’s what I thought the extent of doing music was, and at this point we understand marketing and promotional tools, and promotion in radio and all the different factors that come into it.”

Nu Gruv Alliance released Zion I’s first album, Mind Over Matter in 2000 to substantial acclaim. Deep Water Slang followed in 2003 on Live Up/Raptivism, but failed to propel them across the multi-demographic divide.

“Mind Over Matter and Deep Water Slang came out on different labels, and those projects didn’t necessarily go as well as they should’ve,” says Amp. “So when we had the opportunity, we wanted to have all control over our product.”

Independent success requires not only control of the product, but control of the live crowd as well. The tour hustle pushed them onstage amongst the inimitable Kool Keith, the lung-capacious Lyrics Born, the funky human Del, the three plugs De La Soul, the misnomered Jurassic 5, the mighty Mos Def, and the legendary Roots crew. Zion I has also been billed on the MTV2/Mountain Dew Circuit Breakout tour for the past two years.

This allowed them time to develop an album that truly reflects their current living situation.

“With this album, we wanted to purvey the true sense of hip-hop and what it is to us as individuals, without pretense, without gimmicks” says Zion. “This is how we live, this is our daily experience of life. And hip-hop is our life, so this is our offering. It’s artwork that’s true, and it’s a living work, it’s a body of work because we live it and we give it to people so they can experience it. It’s just true art for art’s sake for people to enjoy and get a good vibe from.”

The artists that Zion I recruited to assist them in crafting True & Livin’ are of the same ilk: genuine. The Gift of Gab, Del, Aesop Rock, Talib Kweli, and Fred Hampton Jr.; each lend their respective voices and visions.

“We wanted to have something with like a different flavor,” explains Amp. “The emcees we have on this album are really tight and professional, so we up our game to make sure the music was good enough to match with them.”

The music’s always been good, albeit different, but it’s the variety of sound that gives Amp’s beats distinction. From Mind Over Matter’s drum-n-bass influenced percussion to Deep Water Slang’s synth-funk basslines, his technique remains simply his.

“I think with Deep Water Slang I used more live instrumentation in terms of like keyboard and that type of stuff, but on this album it’s more like drums, guitar, bass–like the real basic type of stuff, not as much synthesizer stuff,” says Amp. “So it’s just a different type of approach.”

Zion’s approach remains true to himself, rooted in his surroundings, as exhibited on “The Bay”: We hardly get the love ‘cause we close to L.A. / we got our own slang, but everybody took it…

While artists like Too Short, E40, Paris, Hieroglyphics, and Living Legends have created various aspects of substance, swagger, slang, and sales, they’ve been oft-overlooked as innovators.

“One of the main things we feel is that bein’ from the Bay Area like we had a lot of shine in the early ‘90s through maybe the mid-’90s, and after that attention was definitely taken away from the Bay,” says Zion. “New York and L.A. definitely (and Atlanta now) are hubs of music, but I think it’s pretty well known that the Bay Area’s a place where there’s always been a lot of creativity and progressive thought. But still, right now we’re definitely not getting as many spins or people aren’t getting signed out of the Bay.”

Though might take a minute to develop into financial success, the independent route develops character and a strong work ethic that might otherwise never come into fruition.

“There’s young guys comin’ up, there’s older dudes who have more knowledge, and it’s like I think that music is all about learning to master yourself, to communicate your life experience so somebody else can feel you,” says Zion. “I don’t think you’d ever really master that, I think it’s a continual process. So it’s a blessing, but it’s hard work too… You have to kinda go inside yourself and find that space, and learn what it takes to make dope art.”

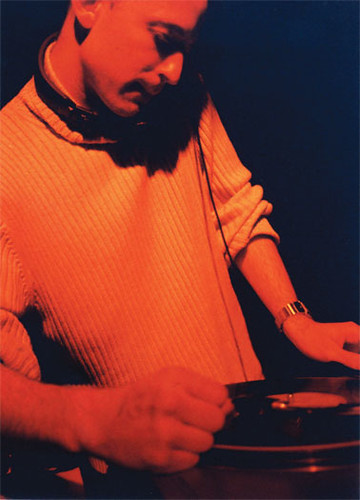

Mixmaster Mike

By Charlie Russo

Deep in the annals of hip-hop history, the origin of the deejay’s scratch is filed under the year 1975 and reads like this: “Eleven years old and practicing deejaying on his older brother’s turntables, Theodore Livingston grabbed for the record as his mom shouted at him to turn the music down. Hearing an odd scratching sound through his headphones as the vinyl moved in his grasp, Theodore knew he was on to something.” Livingston eventually became known as Grandwizard Theodore and was credited as the inventor of both the scratch and needle drop techniques.

Thirty years later, hip-hop has begun to outsell rock music in America, and early forefathers such as Grandwizard Theordore have been succeeded by a lengthy list of turntable talent: DJ Premier, Q-Bert, Z-Trip, Cut Chemist...and of course, Mixmaster Mike. These names may not necessarily be classified as early inventors, but are sure to be remembered as major pioneers all the same.

That said, Mixmaster Mike may very well be remembered as the John Coltrane of turntablism: a musician who caused a quantum leap in the evolution of an already developing art form.

As a three-time DMC world deejay champion as well as the frequently fourth Beastie Boy, Mixmaster Mike cites the road back to the founders as the way for hip-hop to move ahead. ”hip-hop is in a state of re-evaluation,” he explains, ”People need to look back to how hip-hop formed in order to move it forward. I always revert to Grandmaster Flash, The Cold Crush Brothers, and—of all inspirations—to Grandwizard Theodore... back to when hip-hop was a lot of fun.”

It’s not surprising to hear the Mixmaster place emphasis on the old school’s upbeat brand of hip-hop. Anyone who has seen Mike perform knows that amongst all the scratch & whir wizardry, the cut-ups of an eclectic music library, and the barrage of beats... the Mixmaster just knows how to bring a party.

It’s a fact that Bay Area residents were aware of Mike long before he signed on with the Beastie Boys. Though he no longer lives in Northern California, it was during his time here in the foggy Bay that Mike truly became the Mixmaster.

“The Bay Area is and has always been underground,” Mike says in assessing the area’s place in hip-hop culture. “I know my boys Q-Bert, Shortkut and those heads are definitely holding it down,” he adds, “so I’m sure that I left the Bay Area in good hands.”

No arguments there. When it comes to his cohorts around the Bay, good hands are not hard to come by. After the string of DMC championships in the mid-’90s, Mike had joined forces with Yoga Frog, Q-Bert, Shortkut, and D-Styles to form the Invisible Skratch Picklez; the deejay wrecking crew that put the Bay Area in the forefront of the ever-expanding art of turntablism.

Though the Picklez have since disbanded, the Mixmaster still has the itch to keep on scratchin’. In addition to his key role on the latest Beastie Boys’ release To the Five Boroughs, Mike recently unleashed his own mixmonster, Bangzilla.

“This album was like 3 years in the process,” he explains. “I made it in different parts while in many different places - on tour, on planes - and then I tied it all together.”

Bangzilla is certainly an altered beast, showcasing a wide range of beats and scratching techniques, as well as samples that evaporate just as you’re on the verge of recognizing them. On a more subtle level, the dizzying collision of soundscapes seems to have an underlying theme, often coming across like the soundtrack to battles in a galaxy far, far away. “I had 14 tracks to work with and to think about different ways to manipulate music,” Mike says. “I never went about making this album as a concept album... it just came out that way.”

The balance between solo projects like Bangzilla and his role as the Beasties’ beat boy is a particular distinction, one that Mike characterizes as totally different worlds. “It’s like split personalities going on,” he says. “As a solo artist versus being in the group and adding my take on the songs.”

More than just in the studio, it is a contrast that Mike notices considerably in the live arena. ”Doing solo shows you have to hold up your audience,” he explains, “it takes a lot of endurance to do an hour-long show with non-stop tricks. Scratching with the boys I can choose my spots and give the show a flow.”

And though he may no longer be an official resident, the Mixmaster continues to reflect the Bay Areas contribution to hip-hop as a whole: rarely center stage, but still providing the hottest moments of the night.

Afrika Bambaataa

Interview By Bella Bakrania, Bayeté Ross-Smith, & Eddie Mariano

Though hip-hop may be a child of many parents, Afrika Bambaataa taught hip-hop its first steps as a movement. Not long after Kool Herc first put two turntables together, Bambaataa used the music to bring rival communities together. To this day, hip-hop’s original gangsta continues to prove that music can be a catalyst for peace, unity, and social change.

Bella Bakrania: It’s always a pleasure and kinda crazy to hear all the ‘80s tracks rocking the younger crowds once again. How do you feel about that, with your span in hip hop and being able to rock these crowds of many different generations?

Afrika Bambaataa: So many deejays have gotten into the apartheid of becoming a deejay. They say, “I am a ragga deejay, I am a hip-hop deejay, I am a trance deejay, I am a salsa deejay,” instead of just One Nation Under a Groove like George Clinton say. I remember when the techno scene was happening big and the early raves started, I used to go there and there would be 20 something deejays and they all sound the same, so I used to come and break the whole momentum, with REM “Losing My Religion” and going down to some funk and bringing it all the way back up to techno for the next deejay to take on. I was always like that. Trying to bring a whole bunch of records out and play all across the board. Trying to keep that dance scene alive in all styles of music since all music is really dance music. Everybody has got all caught up – “Dance music is only techno or house music”. No, all music— if you can dance to it—is really dance music.

BB: Tell us about your new album out—Dark Matter Moving at the Speed of Light [Afrika Bambaataa and the Millennium of the Gods]—about putting it together and the people you worked with.

It took 3 years in the making. I worked with a lot of these other great recording artists who are also producers that I enjoy a lot. Like Uberzone, Sharaz, Strictly Jeff, Boogie Brown—who was part of my group Hydraulic Funk and also used to be part of the Peech Boys back in the days— and a new young producer coming up DJ Hektek, Dukeyman from the Baltimore Breakbeats, and Gary Numan. It was great honor working with Gary Numan; it was just fun working with all these guys... And a new production team called Fort Knox Five. If you see their records, jump on them ‘cuz all their stuff is slammin’. It was great working with all these people putting out an Electro-Funk album because people were asking for it. I’ve been doing techno, hip-house, flamingo, so I had to come back and do my roots: up-tempo hip-hop.

BB: The album starts out with a tribute to the Indian musical influences. That’s a nice nod to the heavy music production that happens across the world, and has been happening, but people don’t necessarily know about it or tune in to it. Do you play much multi-lingual hip-hop?

Most definitely. I have been playing hindi/punjabi mixes for a long time. I got all the movies and they love it in Africa—the roots of India is Africa too—it’s all one family, we all come from the drum. I play everything. France to Indian style. Spanish to Italiano. There’s different music that I play from different people, sometimes with the instrumentals, sometimes with the languages. In L.A. we was killin’ the hindi remix of Dr. Dre. I went down to Singapore they were going crazy with the hindi mixes.

We got to always respect each others’ culture. That’s my thing. When I travel, I go among the people, I visit different religious places, I go with spirituality. I am not one of them so-called stars that sits in the hotel and says “gimme this, gimme that, gimme a limousine”. I get in cars that are messed up. I go on the train and go visit ‘they houses, and that’s how I understand what’s going on from place to place. I even help out on certain interviews and things and ask everybody, “why don’t you have a community center for the youth?” and start causing a movement in the country to get certain things for the youth.

Travel is a blessing from the Creator, to be among all these different people and places, and to get that vibration, that’s what [gave] the record that vibe, a lot of people tell me the record is a feel-good record with the sitar and all that.

BB: From your span in music, you can talk to people through music—to anyone, of all generations, races, and places.

I just mix it all up, that’s what keeps the vibe going on that floor. Everything is based on that funk. If it ain’t funk, it ain’t happening. Gotta keep that funk alive.

BB: What other kinds of musical changes do you see happening in hip-hop?

I always tell people watch out, this is a very dirty game. James Brown once told me the music industry is 95% business and 5% entertainment. You always gotta be on your p’s and q’s cuz they did a lot of robbing of the early hip-hop groups, as well as the early soul, rock and roll, and reggae groups. It’s still going on now. Now with satellite [radio], it’s really crazy now. The internet’s going to wipe out a lot of stuff anyway, it’s wiping out a lot of these production studios. I did music with Muskabeatz and he came to NY and he did a whole album with me and the Biz Markie, Wu Tang and all in one day in a hotel room on a laptop, that bugged everybody out. People wasted all their crazy money going to a studio. Now you got ProTools.

BB: How do you embrace stuff like the internet and video?

We were always into what we called the electro or the technology side. When we came with Planet Rock in 1982 and we started traveling with all these synthesizers and beatboxes the unions got nervous and attacked us because a lottta people were losing their jobs. But who is better to program drum beats than a drummer? So learn the technology and don’t get mad at it. You’re always gonna have some purists. You’re gonna have people who wanna go with the digital age. It’s a balance between Yin and Yang, negative and positive, agreeable and the disagreeable.

Bayeté Ross-Smith: When you were actually making the songs for Planet Rock, did you have any idea that it could become the type of thing that moved so many people for so many years to come?

I thought it would do its thing for that year, grab a black and white community, then when I saw it snatch all different nationalities across the world it really blew my kind. Then we did the other two records after it, then we did World Destruction with Johnny Lydon of PIL. To see it still last this long and still played to death like it’s a new record and all these remixes you know that’s an honor in itself. I be amazed at how people just chop that record up in so many different ways and make it just as funky as the original.

Bella Bakrania: I’m scared to see how many records you have – you must have thousands just stockpiled. How do you manage? And only you must know where everything is.

They’re in the Dungeon, the Graveyard, and the Bat cave. If I can’t find it I just buy it again. You know that record All This Love by DeBarge? I bought that at least 5 or 6 times! ...I see it, snatch it up and hope it don’t get lost again. I be buggin’ that I can find some things. Most people are trying to run away from vinyl but thanks to hip-hop and dance deejays, they’ve kept it alive. A lot of companies are releasing a lot of these old groups again. Some of these groups are even starting to travel again cuz people are rediscovering the [their] music.

Eddie Mariano: As one of hip hop’s founding pioneers how do you feel about the state of hip hop today?

Well it’s good that you got a lot of brothers and sisters who are becoming millionaires or thousandaires. A lot of people are traveling outside of where they lived, if they lived in the ghetto or the suburb. People gotta look at these people that say hip-hop or these so called radio stations who claim to be hip-hop and R&B, that they really don’t know what hip-hop is, and when they’re playing records they just say “rap”. They forget about the deejays, emcees, breakers, aerosol graffiti writers, and even the fifth element, knowledge.

I think a lot of the rappers have always been saying say we got to form a united front where we can deal with our own problems, our own hip-hop police, and handle our own different beefs that people have, talking about westside/northside/eastside/southside and all that type of foolishness. To even watch the industry from trying to rob you and get some health benefits for a lot of the people that are in hip-hop, to take care of themselves or their family if they get sick.

If you’re gonna be a gangsta rapper, then you better have a gangsta doctor and a gangsta lawyer to take care of your gangsta ass, and a hip-hop judge to be there so when you go there you can throw your gangsta/hip-hop mix sign and symbols and you can get your gangsta ass off. If we are going to claim to be a nation and a culture internationally then we got to start thinking like that. We are seeing that Zulu Nation in this Millennium is all about law, finance, and gettin’ you some land, cuz things are gonna get real funky in this Millennium.

Bella Bakrania: It’s ugly. I feel like a lot of new hip-hop is dividing women and men, it’s just music for strip clubs with videos to match. It’s ugly for the kids.

That’s right. What is that teaching the young kids? You got a 4 year old talking about gettin’ down, “lemme go downtown and get low.” Some people got knowledge and know that but they’re being told they won’t sell music if they’re not doing this. So it’s up to the people to get the word in the street and to call these stations and complain, and hold these program directors accountable to the people. Clear Channel wanna run it by and control things, people gotta get in their ass. It’s coming back to that media monopoly. If we’re still sleeping in that Matrix state of dream, going into—as the Bible say—the Land of the Lord, then you will be taken for that slave and that zombie and next thing you know your mind will belong to the Television. And it’s gonna get deeper as time goes by.

Cops vs Lawyers: RIAA vs Semiotic Democracy

Image by Granger Davis

Image by Granger Davis By Mike Conway

The creative landscape is changing. Technologies like Pro Tools, the iPod, and peer-to-peer networks have become mainstream in the digital age, creating a wild frontier of sorts in music. Rather than struggling to break into radio, musicians can find a mass audience without a major record deal. These technologies are fostering the rise of “semiotic democracy”—where more and more people are no longer passive consumers of mass media, but active participants in creating culture.

The music industry is part of a waning guard, and it fears it will be eclipsed by this new landscape. But the industry refuses to simply take a bow, or even roll with these changes. Instead, it has released the hounds of law onto the backbone of semiotic democracy: the internet.

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) is currently policing digital networks that distribute copyrighted material for free; and it is dead serious. It went after a deceased woman for downloading songs in her twilight years. The RIAA also has a case before the Supreme Court in an attempt to quash peer-to-peer networks. Just like 9/11 paved the way for the PATRIOT Act to “adjust” civil liberties, the RIAA is enforcing copyright infringement to tame the new creative frontier.

Sadly, one of the heaviest influences on copyright law is the lobbying power of the “creative” industries. William Fisher III is a professor at Harvard Law School and a leading scholar of copyright law. He attributes some of the major changes in copyright to “concentrations of economic power.” The life of a copyright is a classic example. In 1998, the copyright for Mickey Mouse was about to expire, making the Disney icon public property. Dr. Fisher says “Disney would have lost a lot of licensing revenue if Mickey Mouse had fallen into the public domain. [So] Disney and many other organizations prevailed upon Congress to extend copyright” from 50 to 70 years.

The RIAA qualifies copyright in lofty terms. Their website states that “to artists, ‘copyright’ means the chance to hone their craft, experiment, create, and thrive. It is a vital right, and over the centuries artists have fought to preserve that right.” But now, in the 21st century, copyright can also encumber artists in their creative process. Putting together mixtapes or samples continues to be tricky for a number of reasons. Dr. Fisher gives two. He says “sampling is one of those zones where the power of a copyright owner gets in the way of successive layers of creativity.” Secondly, Fisher says, “there doesn’t exist a comprehensive copyright registry; so even if you’re perfectly willing to pay for permission to use other people’s works creatively, you can’t find the owner.” The result, according to Dr. Fisher, is that copyright law “is closing off an entire source of new works [and] depriving people of the creative experience.” So despite what the RIAA says, copyright and creativity have yet to shake hands.

But the current copyright regime fits neatly into their ongoing litigation against certain peer-to-peers. Mitch Bainwol, the RIAA’s chairman and CEO says free peer-to-peers follow a “parasitical business model” that “robs songwriters and recording artists of their livelihoods, stifles the careers of up-and-coming musicians, and threatens the jobs of tens of thousands of less celebrated people in the music industry.” And that argument holds a lot of water with many musicians, who believe that for art to have any continuity, artists should be compensated for their work.

But within the recording industry lie several common practices that are quite anti-artist. Work-for-hire and controlled composition clauses can snatch the cheese right from an artist’s mouth. Plus, the artist and the copyright owner are usually two different entities, and they are often at odds.

Copyright is never as simple as “once you create it, it’s all yours.” In any given recording, there are two copyrights: one for the song as it is composed by the artist(s), and another for the song as it is recorded. Many times, neither copyright is held by the artist, or at best he/she will hold a fraction of one, leaving the artist with little control over their own work. In 1998, Public Enemy posted free MP3s of their forthcoming remix Bring the Noise 2000 on their website. The recording label, PolyGram, had considerable share in the album, enough to sue PE and force them to remove their own songs from their official website. PolyGram’s copyright had been infringed.

In theory, the RIAA is right to stand up for the artist and the “thousands of less celebrated people in the industry.” But its legal crusade is as consoling to artists as a crying crocodile. After all, the recording industry is a business like any other; it will do everything in its power to sustain itself. It’s more likely that the industry’s fight on filesharing is about keeping its monopoly relevant than it is about stopping illegal downloading.

Instead of marching on the halls of high government and patrolling fledgling technologies, the recording industry can ensure its own relevancy by bringing justice into the music business. Espousing contracts that empower artists with more say over their legacies is a start. If the RIAA extols copyright as a guardian of creativity, they should develop an accessible database of copyrights to stimulate new forms of creativity. American culture has always been a product of the people. Now that technology and new media has caught up with the diversity of our voices, the industry should step back and listen.

Beni B

By Jesse Ducker

Beni B came to the Bay Area with plans of getting a degree at UC Berkeley. He ended up creating ABB Records, a label that has helped spur the rise of the new independent hip-hop sound through the late 1990s and into the 21st Century.

Beni B, a Los Angeles native, moved to the Bay Area in 1983, just as hip-hop was heating up on the West Coast. “This is a time when Too Short was pioneering with his brand of street marketing,” Beni B said. “At the time, no one had an inkling that it would grow to what it’s become. It was just a way of life: get out there and hustle your tapes. We never had that whole entertainment industry here. So when artists put their music out, they just used a different approach.”

Though Beni says this Bay Area spirit of independence didn’t directly inspire him to create ABB Records, the label has certainly followed the same blueprint as many Bay Area pioneers: find your core audience and tailor the product to meet their needs. ABB Records began as a straight-up hip-hop vinyl label. When the first ABB 12” dropped in 1996, the general consensus was that vinyl was on its way out. Still, ABB has produced vinyl almost exclusively since its creation, releasing over 50 titles on wax to date.

And even though it’s based in the Bay Area, ABB has put out music originating from all over. Their roster includes artists like Dilated Peoples, Defari, the Sound Providers, and Joey Chavez (all from Los Angeles), Little Brother (South Carolina), Foreign Legion (San Jose), Superstar Quamallah and 427 (Oakland), Planet Asia (Fresno), Consequence (New York), Jay Dee and Frank N Dank (Detroit), and Arcee (Toronto). They’ve also expanded beyond hip-hop, even adding a few R&B artists for the ABB Soul off-shoot, including crooner Peven Everett.

Beni says ABB puts out whatever he’s feeling. “I just look for the potential, do I feel it, and can I work with it,” he says. “It’s like: your shit is hot or your shit is not hot.”

Beni B’s involvement with college radio sparked his desire to run a record label. In 1987, he started his first show on KALX, the radio station for UC Berkeley, and stayed rocking on the radio for the next decade. “I had always been into the music, and the involvement in the radio show was just an outgrowth of the music. My whole philosophy to doing my show was that I wanted to expose people to different music.”

Being a deejay also helped Beni learn the ins and outs of the music biz. Over the years he was able to track the career path of the average artist who came through to hype their shit. “I was seeing the big picture,” he said. “I would watch them come when they were little, come through and be big, then fall off and come through again.”

Beni said he first created ABB in order to help his fellow Cal graduate/homeboy MC Defari get his shit out there. Beni had known Defari for years; he co-hosted many of Beni’s shows at KALX. The two stayed cool even after Defari went to Columbia University for graduate school.

In 1997, after years of watching Defari put in work to get his music out there, Beni took matters in his own hands and pressed-up Defari’s first single “Bionic,” b/w “Change and Switch.”

Defari then told Beni that his producer, Evidence, also had his own group, Dilated Peoples, which was also struggling to get their record out. Beni B heard the material, and decided to release the Dilated’s single “Third Degree,” b/w “Confidence,” and “Global Dynamics.” The rest is history.

Beni has had the uncanny ability to put out records that become underground classics. Take ABB’s two most successful 12”s, “Work the Angles” and “Rework the Angles” by Dilated Peoples. Now, six years after releasing the records, Beni B still sends copies of the record to places as far away as Switzerland and South Korea. He’s lost track of how many different pressing he’s done of the records.

Both of ABB’s first artists have remained loyal to the label. Even though Dilated has released three CDs on Capitol Records, they still release all of their vinyl through ABB Records. Defari also remains tight with the label; he recently released an album as part of the Likwit Junkies (featuring him and DJ Babu) through ABB in March. So what is it about ABB that keep artists them coming back?

“We stand behind our artists,” Beni says. “We get in there and we’re not afraid to get our hands dirty. I’m not afraid to carry records in my bag and pass them out to people. And it gets to the point where we’re putting out better and better records. It may get to the point where we’re the premier label and distributor here on the West Coast.”

Beni also predicted great things when Little Brother’s tape came across his desk. Beni was so confident in the group that he chose their first album, The Listening, to begin ABB’s foray into CD distribution. Before, ABB had dealt exclusively in vinyl. It turned out to be a sound investment, as the album picked up a serious underground following and was soon being championed by the likes of Pete Rock and ?uestlove.

However, Beni said doing CDs was difficult at times. “CDs are a whole different market,” he said. “Really, it’s about your plan and how you go and turn over every stone and put that together. It’s the type of learning curve where you spend money to learn. So that can be hard. The music business is not very margin-friendly, so you can kind of screw yourself too. [Working with the Little Brother CD,] there were some things in hindsight we could have done differently, but [considering] where it’s going to end up, I’m not mad.”

Beni took what he learned and applied it the label’s next CD release, The Sound Providers’ An Evening With the Sound Providers. Beni sees big things for the production crew. “I think those guys have the potential to really, really do a whole lot,” he said. “This album, in less than a week, shipped 10,000 units.”

There’s a lot more on ABB’s plate. Beni signed Liz Fields, a Philly-born, Los Angeles-based singer to ABB Soul and Big Tone, a Detroit-based MC. Beni hopes they’ll all reach the same levels of fame attained by artists like Dilated, Defari, and Little Brother

Though Beni would eventually like to get back to his radio roots, he’s more than happy with the way things have gone for ABB. “I wouldn’t trade this for anything. Being able to watch groups like Little Brother, and see where they started and [where] they’re going to end up [is great]. To see their ability to touch people, that to me is worth more than anything.”

Beni B came to the Bay Area with plans of getting a degree at UC Berkeley. He ended up creating ABB Records, a label that has helped spur the rise of the new independent hip-hop sound through the late 1990s and into the 21st Century.

Beni B, a Los Angeles native, moved to the Bay Area in 1983, just as hip-hop was heating up on the West Coast. “This is a time when Too Short was pioneering with his brand of street marketing,” Beni B said. “At the time, no one had an inkling that it would grow to what it’s become. It was just a way of life: get out there and hustle your tapes. We never had that whole entertainment industry here. So when artists put their music out, they just used a different approach.”

Though Beni says this Bay Area spirit of independence didn’t directly inspire him to create ABB Records, the label has certainly followed the same blueprint as many Bay Area pioneers: find your core audience and tailor the product to meet their needs. ABB Records began as a straight-up hip-hop vinyl label. When the first ABB 12” dropped in 1996, the general consensus was that vinyl was on its way out. Still, ABB has produced vinyl almost exclusively since its creation, releasing over 50 titles on wax to date.

And even though it’s based in the Bay Area, ABB has put out music originating from all over. Their roster includes artists like Dilated Peoples, Defari, the Sound Providers, and Joey Chavez (all from Los Angeles), Little Brother (South Carolina), Foreign Legion (San Jose), Superstar Quamallah and 427 (Oakland), Planet Asia (Fresno), Consequence (New York), Jay Dee and Frank N Dank (Detroit), and Arcee (Toronto). They’ve also expanded beyond hip-hop, even adding a few R&B artists for the ABB Soul off-shoot, including crooner Peven Everett.

Beni says ABB puts out whatever he’s feeling. “I just look for the potential, do I feel it, and can I work with it,” he says. “It’s like: your shit is hot or your shit is not hot.”

Beni B’s involvement with college radio sparked his desire to run a record label. In 1987, he started his first show on KALX, the radio station for UC Berkeley, and stayed rocking on the radio for the next decade. “I had always been into the music, and the involvement in the radio show was just an outgrowth of the music. My whole philosophy to doing my show was that I wanted to expose people to different music.”

Being a deejay also helped Beni learn the ins and outs of the music biz. Over the years he was able to track the career path of the average artist who came through to hype their shit. “I was seeing the big picture,” he said. “I would watch them come when they were little, come through and be big, then fall off and come through again.”

Beni said he first created ABB in order to help his fellow Cal graduate/homeboy MC Defari get his shit out there. Beni had known Defari for years; he co-hosted many of Beni’s shows at KALX. The two stayed cool even after Defari went to Columbia University for graduate school.

In 1997, after years of watching Defari put in work to get his music out there, Beni took matters in his own hands and pressed-up Defari’s first single “Bionic,” b/w “Change and Switch.”

Defari then told Beni that his producer, Evidence, also had his own group, Dilated Peoples, which was also struggling to get their record out. Beni B heard the material, and decided to release the Dilated’s single “Third Degree,” b/w “Confidence,” and “Global Dynamics.” The rest is history.

Beni has had the uncanny ability to put out records that become underground classics. Take ABB’s two most successful 12”s, “Work the Angles” and “Rework the Angles” by Dilated Peoples. Now, six years after releasing the records, Beni B still sends copies of the record to places as far away as Switzerland and South Korea. He’s lost track of how many different pressing he’s done of the records.

Both of ABB’s first artists have remained loyal to the label. Even though Dilated has released three CDs on Capitol Records, they still release all of their vinyl through ABB Records. Defari also remains tight with the label; he recently released an album as part of the Likwit Junkies (featuring him and DJ Babu) through ABB in March. So what is it about ABB that keep artists them coming back?

“We stand behind our artists,” Beni says. “We get in there and we’re not afraid to get our hands dirty. I’m not afraid to carry records in my bag and pass them out to people. And it gets to the point where we’re putting out better and better records. It may get to the point where we’re the premier label and distributor here on the West Coast.”

Beni also predicted great things when Little Brother’s tape came across his desk. Beni was so confident in the group that he chose their first album, The Listening, to begin ABB’s foray into CD distribution. Before, ABB had dealt exclusively in vinyl. It turned out to be a sound investment, as the album picked up a serious underground following and was soon being championed by the likes of Pete Rock and ?uestlove.

However, Beni said doing CDs was difficult at times. “CDs are a whole different market,” he said. “Really, it’s about your plan and how you go and turn over every stone and put that together. It’s the type of learning curve where you spend money to learn. So that can be hard. The music business is not very margin-friendly, so you can kind of screw yourself too. [Working with the Little Brother CD,] there were some things in hindsight we could have done differently, but [considering] where it’s going to end up, I’m not mad.”

Beni took what he learned and applied it the label’s next CD release, The Sound Providers’ An Evening With the Sound Providers. Beni sees big things for the production crew. “I think those guys have the potential to really, really do a whole lot,” he said. “This album, in less than a week, shipped 10,000 units.”

There’s a lot more on ABB’s plate. Beni signed Liz Fields, a Philly-born, Los Angeles-based singer to ABB Soul and Big Tone, a Detroit-based MC. Beni hopes they’ll all reach the same levels of fame attained by artists like Dilated, Defari, and Little Brother

Though Beni would eventually like to get back to his radio roots, he’s more than happy with the way things have gone for ABB. “I wouldn’t trade this for anything. Being able to watch groups like Little Brother, and see where they started and [where] they’re going to end up [is great]. To see their ability to touch people, that to me is worth more than anything.”

Peanut Butter Wolf

By Jesse Ducker

People might still think Peanut Butter Wolf is a strange nom-de-plume, but the producer/DJ/label owner has an undeniable wealth of knowledge of hip-hop and almost all forms of music. So it makes sense that he gets worldwide respect for his skills behind the boards, turntables, and the office desk.

The San Jose native has been into hip-hop from the start, and in the late 1990s, after years of doing acclaimed production work, left the samplers and the drum machines behind to focus on the business side of things. Close to a decade ago, he founded Stones Throw Records, which he runs with his potna, Egon. PB Wolf also regularly represents the label. He often tours with Stones Throw acts or by himself, journeying around the world and doing DJ sets.

Stones Throw is a unique independent hip-hop label. It has put out many hip-hop releases, such as Lootpack, Madvillain (Lootpack producer/rapper Madlib and MF Doom), Jaylib (Madlib and super-producer/rapper Jay-Dee), the acclaimed live-band The Breakestra, and albums by other rappers who are down with the Lootpack (Wildchild, Ohno, Quasimoto, etc.). Later in 2005, Stones Throw will drop an album by mid-1990s NY underground legend Percee P, likely to be produced entirely by Madlib. The common thread through all these releases (besides Madlib) is that they usually take a back-to-boom-bap approach to hip-hop, or they try some way-out, highly experimental shit, like Quasimoto or Madvillain. Releases by the latter two artists at times feel like acid-trips laid on wax.

However, there’s a whole other side to Stones Throw. PB Wolf has used the label to reissue material that he loves. This includes the album Now by obscure, unclassifiable band Stark Reality, The Third Unheard—a compilation of early 1980s hip-hop from Connecticut—and a slough of early 1990s 12”s from artists like Dooley O and Stezo. The label has also put out material beyond the realm of hip-hop, including abstract jazz albums by Yesterday’s New Quintet and Monk Hughes and the Outer Realm (actually Madlib recording under other names). He’s also released Mary Had Brown Hair, a new album by Gary Wilson, an obscure psych-rocker whose only previous release came out in 1977.

In late 2003, Stones Throw released Big Shots by PB Wolf and his best friend Charizma, who was tragically killed 10 years earlier. PB Wolf said he planned to release the album, but needed to wait until the right time. Both PB Wolf’s beats and Charizma’s rhymes have stood the test of time.

Stones Throw has excelled through releasing their brand of hip-hop and music. While some indie “can’t miss” powerhouses like Rawkus have folded, Stones Throw is still going strong. In fact, to commemorate their 101st release, they dropped a Stones Throw 101, which features a DVD of all the videos by artists on the label and a mix CD with PB Wolf himself on the turntables. PB Wolf and Stones Throw have even more fly shit on deck, including a release from Canada’s Koushik, the long-awaited solo album by New York’s Percee P, and a new Quasimoto album, all set to drop shortly.

SHOUT: When did you decide you wanted to run a record label?

PB Wolf: Even when I was producing, I knew I wanted to eventually start my own label. This was true even back when Charizma and I were looking to get a deal. I’ve always been interested in the promotional aspect of things. When I produced for small record labels, I always worked to make sure the local radio stations and stores had the record. I also went to San Jose State University, where I got a degree in marketing with a minor in advertising. So I’ve always been interested in the business-side of things.

After shopping your demo, you and Charizma eventually signed to Hollywood Basic, which, at the time, was owned by Disney. Of course, now the label no longer exists. Did you guys ever consider signing to an independent label?

We wanted to go with an indie label. A major indie like Jive Records or Tommy Boy. This was before Jive was putting out records by people like the Backstreet Boys and Britney Spears. But in the end we went with Hollywood Basic, because they came to us with the best offer. You can try your hardest to get with the labels that you’re interested in, but in the end it’s always best to go with someone who wants to work with you.

But did you have problems with the label regarding the album you and Charizma recorded?

Our music was one way, and people from the label wanted to change it into something else; something more pop. And we didn’t like it. Back then, we were young and felt like we were on top of the world, so we weren’t the most friendly with the label. They wanted us to do stuff like get a lot of outside producers to do remix work. We wanted to do things on our own. And Charizma and I grew up idolizing groups like Gang Starr and Pete Rock & CL Smooth, who did everything by themselves.

Do you miss producing?

I definitely don’t miss producing. That was a different time for me. Now I’m running the label full-time and doing DJ gigs. Hip-hop has changed so much since I was producing.

How so?

Well, to tell you the truth, it’s a little boring to me. I don’t like sounding like the old, bitter cat, but that’s how I feel. I’m really not feeling a lot of the hip-hop out right now. The music industry has been suffering lately, and to tell the truth, there’s very little new music that I like.

But a lot of the stuff that comes out on Stones Throw is hip-hop.

Of course. I still love hip-hop. The Jaylib and Madvillain albums have come out, and we’ve put out albums by Ohno, who’s down with Madlib and the Lootpack, and we’re going to put out Percee Pee. Basically, Stones Throw puts out whatever I like. We’ve put out a new album by Gary Wilson, who put out a psychedelic rock album in the ’70s. I don’t know if the average hip-hop fan is going to feel it, but a lot of my favorite records that we’ve put out people haven’t felt. For example, the Captain Funkaho 45 is one my favorite releases on Stones Throw, but most people don’t understand it.

When you first started the label, did you ever think you’d get to the point where you’d put out 101 releases?

I never gave it much thought. I’m happy that we made it, but I’ve always done it day by day. Nothing has been calculated. I’m glad I’ve been able to put out so many releases in so many different genres, but it’s all been rooted in hip-hop.

Is there anything you learned about running your own label through your experiences with Hollywood Basic?

I’ve learned to work with the artists to make sure that they’re satisfied with the way things are handled. I want them to be fully happy with their albums. I’m pretty hands-off in the whole process.

The only thing I ever have disagreements with the artists about is how long the album should be. A lot of times the artists want the full 74 minutes, and I think you should be able to get your point across in 60 minutes. So sometimes I ask them to get back and try to trim it down to an hour. The Madvillain album was 45 minutes, which was probably the perfect length for the album. There were a lot of songs, but they were all pretty short. The Lootpack album, one of the first full-lengths, was really long. We had to press it up on triple vinyl. And triple vinyl seems a little ridiculous. My Vinyl Weighs a Ton—my album on Stones Throw—was also triple vinyl. Yeah, I should have probably gone back and edited it down.

So are you concerned with selling records? Some of the stuff on Stones Throw, like the Stark Reality reissue, isn’t very accessible.

I’m only really concerned for the artists’ sake. I don’t want to feel like I’ve let people down. We do all of the stuff that other labels do. We get out on the road and promote the records. We’ve got street teams. We do videos. You might not see them on MTV, but we do them. In fact, when we first posted the video for Madvillain’s “All Caps” on our website, we had to take it down because it got too many hits. Our host said they couldn’t handle the traffic.

I only work with the artists I trust. But I’m really picky. A lot of times artists are scared to give me stuff, because they know how picky I am. I’m one of the pickiest people in the business. I won’t put a record out unless I love it. But we do we put out an album a month each year. I really do take this seriously.

With records like the Stark Reality record and the Funky 16 Corners album, Stones Throw is becoming well known for its reissues. Was it always the aim of the label to do reissues? What made you decide to do it?

It was always something I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how to do it. When I met Egon, he was working for a radio show that would track down and interview old-school acts. That’s how the Funky 16 Corners compilation came about. Egon had known a lot of these artists through the radio show. Plus, the success of the Breakestra album made us feel like we could put out an album like that and it would be accepted by the “keep-it-real” hip-hop fan.

So Egon had original copies of the 45s, and we put them together and came out with the album. It was almost like a new release, to some extent, because a lot of these 45s were very limited local press-ups in the South and the Midwest, so they never made it to places like New York or California. They only had runs of like 1,000 copies, so like 99.9% of the population had never heard it before. That’s why the majority of these artists are receptive to us when we contact them and ask them if we can reissue their material. It gives them a second chance to be heard. A lot of their stuff was never heard before.

You get out there more than some people who run record labels these days. Not every label owner goes out on tour and performs with the rest of the artists. What made you decide to tour and deejay so much?

Well, I’m a deejay first, so I like going out there and doing that. But it actually works out well for the label. I can go out there and meet the people who run the stores and nightclubs. There’s also Egon, who works as the label manager and runs the label while I’m away.

What are you feeling these days?

Actually, I’m feeling a lot of the southern bounce music, like Lil Jon and Lil Flip. I’m still a fan of music. I still buy a lot of old stuff. I’ve got most of the hip-hop. A lot of the hip-hop I dig for is the independent gangsta rap stuff that came out in the 1990s after NWA. Like from all over the country. I buy a lot of old house records, a lot of dancehall. You can never have everything, there’s always going to be more to dig for.