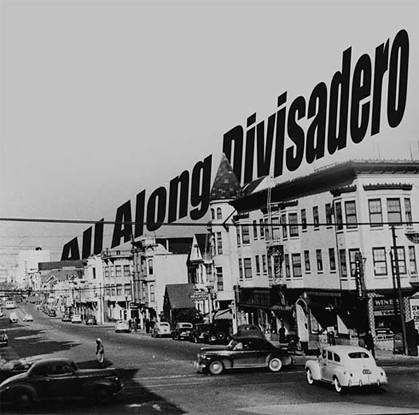

The Age of Divisadero Soul

by Mike Conway

If I could travel anywhere, it would be back in time. I want to go back and see, hear and feel the places and moments we can only study now. Going back in time is not as hard as it seems; many backdrops of the past remain with us. All you have to do is go to those places and imagine the things you know about the past, and you’re there.

I just got back from such a trip, that I took after speaking with Ms. Josephine Robinson. From 1959 to 1977, she and her husband ran a nightclub and restaurant at 543 Divisadero Street in San Francisco. During this period, just four blocks east, the Fillmore Jazz Era was in full swing. Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and countless other gods of jazz played up and down Fillmore. The ‘Moe had a reputation as the Harlem of the West.

But along nearby Divis, a parallel surge of jazz and early soul was blazing. More than just a music scene, Divisadero was its own nation, its own economy, and its own revolution. History has mostly forgotten this street; Ms. Robinson has not.

Though she modestly insists her memory has faded in her old age, she lucidly recalled a lot about her tenure at Club Morocco. Her kind, grandmotherly voice spoke of the many patrons she would occasionally “po’liquor” for. Herb Caen ate there often, and called the Morocco the “Salt ‘n’ Pepper” because it drew both blacks and whites together in their mutual quest for good food, music, and fun. This was at a time when prejudice was the absolute status quo; even in San Francisco, a woman couldn’t serve alcohol in a bar unless she was on the liquor license. Never the less, the Morocco was a place where all kinds of folks could dress up and get some dinner, dance, and catch acts like Ike and Tina, Marvin Gaye, and BB King. Giants’ legendary ballers Willie Mays and McCovey might be eating at the table across from yours.

But the Morocco was much more than a happening joint. It was part of a whole scene. All along Divisadero, you had bars and nightclubs like the Both And, the Bird of Paradise, the Sportsmen’s, and the Half Note. Across the street, at the Harding Theater, Curtis Mayfield played one of his last shows in the city. Up until 1965, folks would dance and parley up and down Divis until 2:00am, then hop over the hill to the ‘Moe and famous places like Bop City, which carried the vibe until the break of dawn.

But more importantly, Club Morocco was one of the many African American-owned businesses. Ms. Robinson recalled that throughout the ‘50s and ‘60s on Divisadero, roughly 75% of all businesses were black owned. It was its own economy of beauty parlors, barber shops, boutiques and, of course, the nightclubs. You could get a haircut, eat a nice meal and dance your ass off to live music, all in a single block.

In 1955, just as the Robinsons were putting together the money that bought 543 Divisadero, the U.S. Supreme Court set the guidelines for desegregation in its Brown II decision. Yet oppression-by-segregation would not just end at the drop of a gavel. Brown II might have been a wonderful development in the Civil Rights Struggle, but it was also wonderfully vague. Blacks might have been free to then find work unimpeded by law, but they had been deprived of such opportunities for centuries. “Sure you can join our union, but—what’s this? No union experience? Sorry.”

That’s where the Robinson family stepped up. To help their community, the Robinsons hired waitresses, bartenders, and busboys—way more of them than they ever needed—so that black folks could get the necessary work hours and go on to get jobs, join unions, gain benefits and live better lives. So when you went to the Morocco, you weren’t just seeing Marvin Gaye or James Brown rock the house, you were seeing a subtle revolution against de jure racism. And with so much wait-staff, the service at Morocco must have been impeccable.

The ‘70s brought the notoriously scandalous “redevelopment” of the Fillmore district. Buildings that housed black families and businesses were being suspiciously condemned for “utility upgrades”; fires would mysteriously destroy others. By 1977, Divisadero was reeling from it all. Businesses folded as pimps and prostitution moved in full time. An ardent Protestant, Ms. Robinson could no longer stomach serving this new clientele. She convinced her husband to sell, just before the avalanche of crack and Reaganomics plowed through.

Tony Bennet is famous for leaving his heart in San Francisco; San Francisco itself often leaves its heart in the past. The forces of change have paved over many subtle charms of this city, leaving us with only the nostalgia for a bygone time. But just the other night, after I spoke with Ms. Robinson, I took a stroll down Divisadero, and imagined myself there, many years before I was born. The streets would’ve bustled with people of all backgrounds, the scents of dinner would be wafting out the Morocco and Curtis Mayfield would be sound-checking at the Harding. Maceo Parker just might drop in later on...

Then, as I steered my mind back to the present, I wondered, “is that type of thing so far off?” Bars and clubs have returned to Divis, why can’t the vibe? Hell, there’s streets like this all over the Bay, why can’t they have it too? We got the music, we just need the venues and events.

Just recently, the former Morocco, now Club Waziema, just got all the necessary permits to do what they always have at that address. Liquor, entertainment, operating ‘til 2:00am: licenses like these eluded the bar for years, until its customers and neighbors began to pressure city and state agencies to cough them up. It’s said over and over that a community working together can make a difference, and it’s true. When a community (hint!) collaborates to promote and support itself, in whatever way, what would it need of any outside help? Would a community then need corporations to create jobs for it? Not really. Would it rely on politicians to slowly dole out rights and privileges to it? Probably not. When we start to provide these things to ourselves, then maybe we could get serious about revolution and independence as a movement.

<< Home