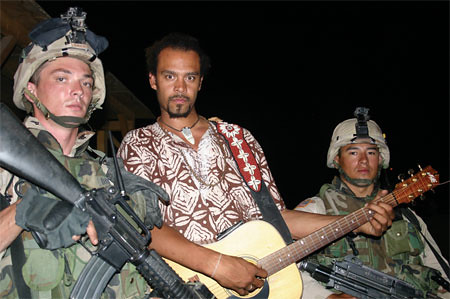

Michael Franti Tours Iraq

As told to Charlie Russo by Michael Franti

Shortly after interviewing him for our first issue, Michael Franti embarked on a trip to the Middle East to get a first hand street-level view of the war in Iraq. Traveling with a small team of filmmakers, Franti played music for Iraqi citizens and U.S. soldiers alike, creating a short documentary along the way chronicling his interactions with those involved in the current conflict.

The resulting film is titled Habibi, a word meaning “sweetheart” in Arabic, and doubling as the name of a song that Franti composed during his travels. Although the film’s completion date is set for the end of the year, Franti took some time to speak with us about his travels and reflect on his time in the war zone...

I had grown tired of hearing about this war through generals and politicians who never take the time to talk about the human cost of the war, and I wanted to talk with the poets and the writers and the taxi drivers and the kids....to hear about their experiences.It was really intense. From the moment you get there you feel the adrenalin and the stress of people that are living in fear and basically never feel safe at any time during the day.... and you quickly become one of those people.

We flew in on a twin-engine plane, and you get over the city of Baghdad and the pilot bends the plane and then does a nosedive-spiral down to the airport. The reason for this type of landing is to avoid shoulder-fired Sans-7 surface-to-air missiles. The Sans-7 is a heat-seeking missile, so it can make an arc back to where you are, but if you’re spinning it can’t find you.

In the daytime, it’s just so crowded on the streets that it’s just impossible for anyone other than a really experienced driver to maneuver around, because so many places have been bombed, and so much traffic has been stopped. At nighttime, actually around sunset, everyone goes back into their house. There are no basics like water in their homes. The electricity only works occasionally for a few hours at a time, and then goes back off again. No one has a job, there is 90% unemployment, and everyone has a gun. People just openly carry guns down the street. Everyone goes inside at 3 or 4pm and then you start hearing gunfire and mortar fire.

We had a lot of interactions. A lot of times I would just chill out on a street corner somewhere and play, or go to a restaurant and have a meal and then play. We would go to the hospital and ask if we could come in and play for the kids. Everywhere we went we were really well-received and as soon as I would start to play some people would come around and just clap. There is really just no music there at all; especially from a foreigner... especially an American foreigner.

We were staying real close to the Sheraton Hotel...which is filled with journalists and U.S. soldiers. There was a little catina were they would all go on their time off, and I played for about 40 soldiers. Well... when I sang the song “Bomb the World”, which goes, “you can bomb the world to pieces but you can’t bomb it into peace.” I was never more afraid in my life...playing in front of 40 soldiers who were holding an M-16 in one hand and a beer in the other. But afterwards they all came up to me and we all talked, and there were two or three of them who said, “I support the war. I’m a patriot. I support our Commander in Chief.” Then about half of them said, “I really wish we would have gone to the U.N. before we came here. I supported the war before I got here and now I don’t see what the point is.” And the rest were like “Fuck this place. Fuck this war. Fuck George Bush.” But every single one of them, more than anything, said that they wanted to go home, and that they felt like sitting ducks. There are about 142,000 U.S. troops in Iraq. In Baghdad alone, they have 4.5 million people.

When the troops first came, they were trying to win a military victory... and they succeeded; they overthrew the government. But now the war is to win the hearts and minds of the Iraqi citizens. But having Abu Gharib, handpicked leaders, no elections, having a lot of civilians that were killed and no water, no electricity and no jobs... you’re not gonna win over the hearts and minds holding an M-16 in your hand, and the troops are aware of that. I talked to some people in the military who were pretty high up the chain of command, who told me that they couldn’t withdraw without first having hundreds of thousands of more troops there. It would be too much of a danger to just withdraw.

So I believe that we’re going to see more and more of the same. As time wears on the situation is gonna become worse both here—in terms of how much were paying for the war, and in Iraq—how much the people are suffering. Eventually the fighting is gonna build up to a point where it is creating almost a civil war situation. They’re gonna have to manage the country and give the Sunnis one part, and the Kurds another part, and the Shiites another part. That’s just my prediction, because I can’t see how America is gonna allow a Shiite government to run that nation. And I dont see how the people of that nation are gonna stand for being constantly shot at.

One final positive thing is that whether it was playing music for the troops or the kids with no legs, or the people on the street, it didn’t matter what the words to the songs were or what the melody of the song was. What was important was that we felt like we were all together in song. And I think that is why God gave us music.

<< Home