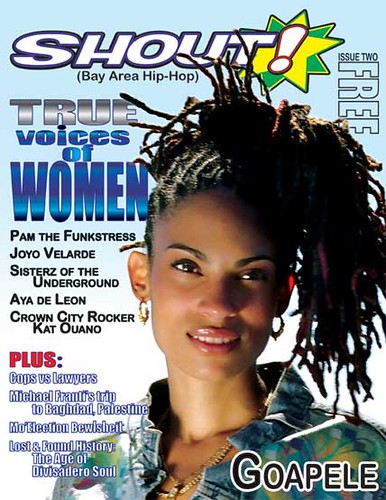

Cops vs Lawyers: SF DA Kamala Harris

Image by Granger Davis. Interview by Mike Conway.

Image by Granger Davis. Interview by Mike Conway. Kamala Harris is San Francisco’s first female DA, and California’s first African American woman to hold the office.

On April 10, 2004, police officer Isaac Espinoza was killed in the line of duty in San Francisco. When a suspect was brought to court, San Francisco District Attorney Kamala Harris refused on principle to pursue the death penalty. Police officers across the country were outraged.

Several news media and alternative publications insist that this dispute has struck a gaping rift between the respective offices between the DA and the police. This rift only seemed to widen into other areas of law enforcement such as prostitution, where the DA’s office is working to change the police’s approach.

SHOUT: Explain your position on prosecuting the murder of Officer Espinoza.

District Attorney Kamala Harris: I am outraged by the cold-blooded murder of 29-year-old Officer Isaac Espinoza. He was a dedicated young police officer who voluntarily put himself in danger to protect the innocent. I must admit that I, too, felt an immediate desire for revenge. I have been a member of law enforcement for my entire career, and so I take personally the outrageousness of violence against a police officer. Wanting an eye for an eye is also one of the oldest and most natural of emotions. But as one of America’s greatest teachers, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., said, “the old eye for an eye philosophy leaves everyone blind.”

The district attorney is charged with seeking justice, not vengeance. From my career in law enforcement and the law, it is clear to me that the death penalty is deeply flawed. [Instead] I have charged this case as a special circumstance homicide, which automatically carries a sentence of life in prison without possibility of parole. And, let’s be clear about that sentence: It means exactly what is says. People who receive this sentence will never see the light of day again.

How will you work with the police going forward?

KH: The police are like anybody else: they want to know what’s going to happen when they put in the long hours. If you have a bunch of police out working the streets, arresting people for certain crimes and then the DA doesn’t charge those crimes, they’re going to be frustrated. It’s irresponsible to not deal with that dynamic. We’re giving clear guidelines about what we will charge, and what we won’t charge, and in that way, everybody is on the same page.

Lessons learned about media relations from the Espinoza murder case:

KH: The media and the public has been conditioned to respond to bells and whistles—there’s a lot of guns and violence, and that’s what sells.

How ar you different from former DA Terrence Hallinan?

KH: I like to think of it not just as differences between me and my former opponent, but also as a new era and a new direction based on the current issues and problems to be solved.

For example, I’m thinking a lot about what we are doing about quality of life crimes—what can we do to have a drug policy that is appropriately strict when we’re seeing repeated sales of drugs, but at the same time, [a policy] that is appropriately compassionate when we’re talking about things like Medical Marijuana. I don’t see these things as being mutually exclusive; I don’t think we have to talk about the criminal justice system in a way that being compassionate means being soft on crime.

I came to the office and we had a backlog of 74 homicide cases, some as old as four years, and in my first six months in office, we were able to put a dent in that backlog and reduce that number by 36%. Within six months, we tried as many cases as we did all last year. It took making those cases a priority. I talked with judges and police letting them know we’re going full speed ahead on these cases, and everyone got on board. It was a welcome change. Anybody would admit there should be consequences when you commit a crime to harm someone. Those consequences should not be retaliation in the streets; it should be the consequences that result from the criminal justice system working, which means prosecutors working.

What is your stance on quality-of-life-crimes?

KH: With prostitution, consenting adults should be given certain latitude. [But] it’s a very complicated issue and I’m not prepared to say it should be legalized. When you talk about prostitution, there are many related issues: exploitation, violence and other crimes that surround prostitution. There is the issue of what prostitution does to a community. When it starts to harm individuals and communities, then something has to be done.

Kids are developing at a younger age; there are girls as young as 11 that are fully developed, but as soon as they open their mouths, you know they’re kids. I have instituted policies in this office basically to say that if an adult is having sex with a youth that is being prostituted, we can charge that person with child abuse. It’s literally changing the way we are looking at this issue.

I meet with Market Street merchants and families that live in the Tenderloin—and there are a lot of families that live there—and they can’t walk to the corner, their kids can’t walk to the park without being harassed by drug activity. So that concerns me. They have a right to live in a safe community. So I am taking quality-of-life offenses more seriously.

What’s one thing you’d like the Hip-Hop Community to understand about your organization?

KH: The point of my work is to not only ensure consequences to crimes, but also to protect the most vulnerable people in the community. And often, the people who are most vulnerable may also be people that aren’t the poster-child for sympathy. But that doesn’t mean I buy into that version of who we should care about. I’m prepared to go after people who victimize others which may live a lifestyle that is disliked by society at large.

One of the things that makes populations vulnerable to crime is if they don’t trust law enforcement and if they don’t have the means to communicate with law enforcement. That is just a fact. So the way we have to deal with that is to be present in these communities and to speak to them in their language and also recognize the experience they have traditionally had with law enforcement.

If someone is beating up or kills your brother, shouldn’t you be standing up? Shouldn’t you be saying, “he did it.” We have to dispel the perspective that whoever cooperates with law enforcement must be a snitch. That’s ridiculous. Can you imagine if everyone would come forward? I cannot as a DA charge somebody with the crime of murder without any evidence.